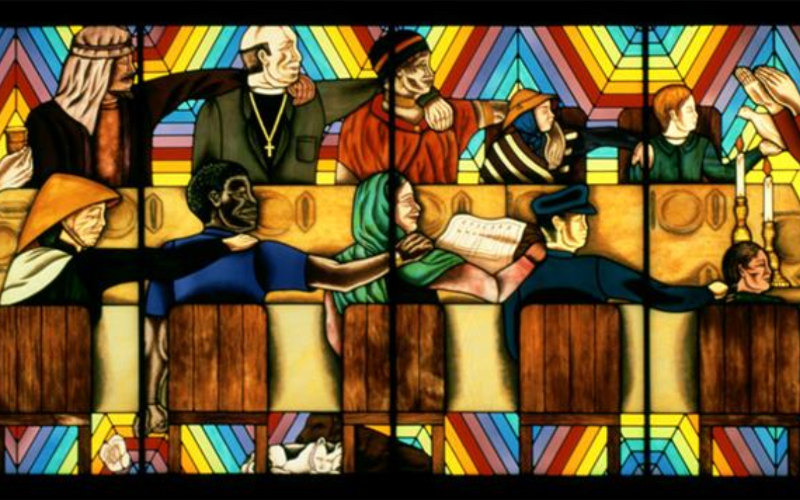

The final image in “the Holocaust Project: From Darkness into Light,” a traveling exhibition that Chicago and her husband, photographer Donald Woodman, created, is “Rainbow Shabbat” (1992).

Their eight-year partnership on this project started in 1985 with a journey through Europe and the Middle East to investigate the significance of the Holocaust in the modern world.

Chicago underwent a journey of self-discovery during which she realized the importance of her Jewish identity and how it shaped her views on the role of the artist and the necessity of producing art with a transformative purpose. It was a journey into the dark as well, which was obviously extremely unsettling on many levels.

The end result was a show that featured both painting and photography along with additional tapestry and glass pieces created by chosen artisans. A vision of a future in which people are united despite differences in age, gender, race, religion, and culture in order to live in harmony with one another and the natural world was what Chicago wanted as the exhibition’s final image. Because, in her own words, “Light is Life,” she decided to depict this vision in a sizable stained-glass installation titled “Rainbow Shabbat: A Vision for the Future.”

During a special Shabbat dinner at friends’ house in Chicago while she and Woodman were on a trip to Israel, the concept for the Rainbow Shabbat as an emblem and a message of hope emerged. As she later wrote: “There were twelve people there: men and women from four different countries, of different ages, and mostly strangers. We all went around the table and told stories, and everyone listened for hours. For me the evening brought up not just feelings about my childhood but also the incredibly warm moments Donald and I had shared with Jews around the world. Being welcomed into Jewish homes during our travels gave us a profound sense of a global community and provided me with an idea for the last image of the project, an image of optimism and hope.”

As they would be during her blessing over the candles, Chicago chose to show the Shabbat service with everyone’s heads turned toward the woman as her husband raises his Kiddush cup and sings his wife’s praises. This condenses the actual sequence of Shabbat events while adhering to its spirit, as Chicago intended.

Additionally, it highlights both the Jewish and the female experiences, arguing that both have the power to change people. The two side panels, which are in addition to the central window, include a prayer in English and Yiddish that is based on a poem written by a Theresienstadt survivor. It reads, “Heal those broken souls who have no peace. Lead us all from darkness into light.”